I dropped out of college twice.

I graduated high school in 2019. At 17, I didn't see a compelling reason to be in school. I had already found something that gave me a sense of agency: building games. What started as a hobby became a source of income, then momentum, then identity. I was making games people actually played, managing servers with thousands of users, tweaking virtual economies, responding to user behavior in real time. I didn't have a vocabulary for what I was doing—no one was calling it "product-market fit" or "user retention curves"—but I was iterating and shipping. It felt tangible. School didn't.

I'd come home from working at a soup dumpling restaurant while being a full-time high school student, smelling like oil and steam, getting off at 10:45 PM and enduring the hour-long D train ride home through empty subway cars. I'd wash off the kitchen shifts, crack open my laptop, and disappear into a codebase, writing Lua until 2 or 3 a.m. I felt like I was getting ahead, bypassing the bureaucratic wait-your-turn model that education seemed to impose. My parents hadn't gone to college and had still built solid careers; I took that as proof that credentials were optional if you worked hard enough. Meanwhile, my sister was crushing it at Cornell, navigating her own path with clarity and purpose. She had figured out how to value academics on her own terms, without needing to crash and burn first like I did. I needed the fall before I could start climbing. At the time, I convinced myself that we were wired differently. That she needed structure, and I needed space.

So I dropped out. For a little while, it felt like control.

The second time I dropped out, it didn't feel like anything. No clarity. No confidence. Just inertia. I wasn't building anymore. I wasn't learning. I was still busy, just circling old instincts. I started to realize that productivity isn't the same as direction. I could make things, but I didn't know why I was making them. I'd lost the feedback loop that used to keep me sharp.

It took a long time to admit that I'd stalled. It took longer to act on it.

Community college

When I re-enrolled at Kingsborough, a community college in Brooklyn, it wasn't with any grand plan. I was out of momentum and figured it was better than doing nothing. I signed up for CS12, a C++ intro course, mostly because it sounded like something I "should" know. I expected to be bored or maybe frustrated, but instead, I felt alert. Not in the way you do when you're cramming or grinding, but in the way you feel when your brain is genuinely awake. The concepts were precise. The rules were unforgiving. But for the first time in years, I wanted to get it right. I stayed after class. I rewrote assignments from scratch just to see if I could do it cleaner. I felt like I was in dialogue with the material, not just going through the motions.

A few months into my first semester, my advisor pulled me aside and handed me a simple note that just said "Suggest switching major to CIS." The message was clear: she thought CS was too difficult for me.

By the end of the semester, I was the top student in the class. That felt good, but what mattered more was the shift in mindset. I wasn't coasting on instinct anymore. I was learning how to learn again. And it made me confront something I'd avoided for years: being talented means very little if you haven't built the structure to sustain it.

Community college forced me to take myself seriously. Not in an inflated, résumé-chasing way, but in the quiet, unglamorous sense of showing up early, finishing problem sets without shortcuts, staying after class to help someone else debug their loop. I became a CS tutor, joined Phi Theta Kappa, and started building real relationships with professors. I wasn't unique in doing any of this. The best students at CC weren't chasing prestige. They were rebuilding, like me. They weren't waiting to be discovered. They were doing the work.

I met some really smart people in that tutoring center, solving proofs on scratch paper, passing around half-eaten bagels, grinding through textbook problems in silence. A lot had gone to Brooklyn Tech or other competitive high schools, had burned out, dropped out, or been derailed by things no one writes about in admissions essays. We taught each other how to care again.

During that time, I also interned at Shared Studios. I drove to CC but took the train to work. That summer, I was taking 8 credits while interning full time. One class required in-person attendance, which meant early mornings, long days, and hours lost to commuting. It was exhausting, but it helped me figure out what I could handle when the motivation was internal. And more importantly, it made me realize I didn't want to live in that kind of overdrive forever.

In my final semester at Kingsborough, I took Calc II with Professor Davydov. He was known for brutal exams. I failed the first one, scored a 60, and for a moment thought I had slipped back into old patterns. But by that point, I'd learned how to learn. I didn't spiral or withdraw. I studied smarter, asked better questions, and took ownership over every mistake I made. I ended the class with an A.

Transfer season

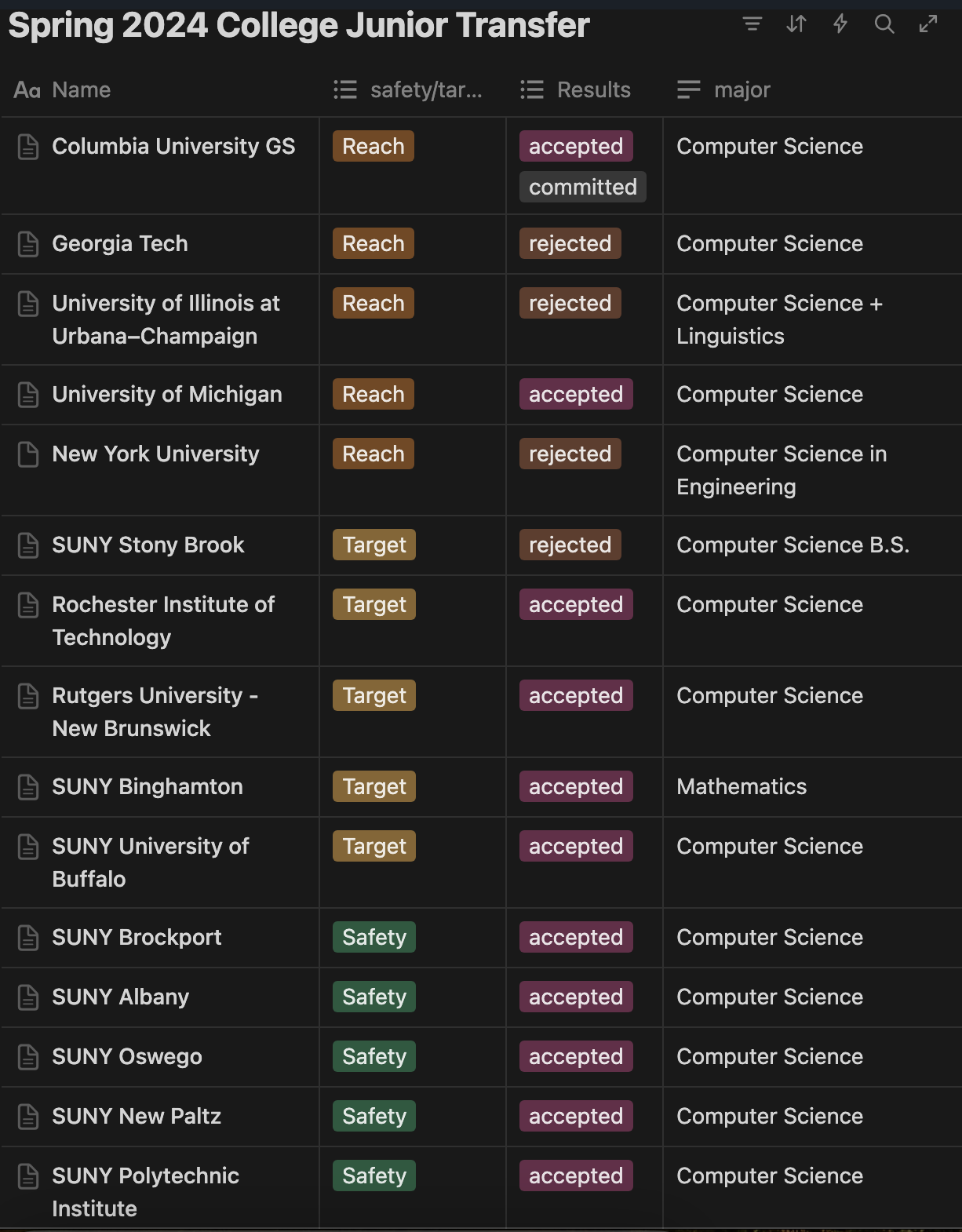

When transfer season came around, I approached it less like a dream and more like a system design problem. I got help from Ariana Davarpanah at TransferTea, who had somehow pulled off the near-impossible feat of transferring from community college to Stanford before doing ops at Robinhood. I also worked with Brandon Tineo, a college consultant who was sharp as hell—Harvard grad, SWE at Google and PayPal. I mentioned Columbia and UMich as reaches. He gently nudged me toward safer picks. I understood why. Two dropouts. Community college. A 2.3 high school GPA. Even with a steep upward trajectory, I was still a statistical long shot. But I applied anyway. I was absolutely trying to prove something—that I could make it despite everything. I just felt like I had finally earned the right to ask for more.

What comes after

I chose Columbia, partly to stay close to home, partly to see what I could become in a space where the default expectation was excellence. I wanted to be tested. But when I got there, I didn't stop chasing. I still felt like I had to prove I belonged, so I filled my time with more. More projects. More internships. I didn't know how to slow down. I wasn't even sure what slowing down would mean.

That pace took me to Stoke Space, where I'm currently working on the Fusion (now Boltline) team, building internal tools and parts configuration systems. It's the kind of engineering most people never see, but it shapes how engineers do real work. This fall, I'll be joining SpaceX to work on the Application Software team. And yet even now, with everything I thought I was chasing finally within reach, I catch myself looking ahead to the next thing. The next project, the next milestone, the next validation.

I used to think that once I got into Columbia, I'd feel like I made it. Then I thought the same about Stoke, then SpaceX. Every time I reached one summit, I was already scanning the horizon for the next. That instinct to keep moving helped me survive CC, helped me push through burnout, helped me compete. It also made it easy to forget why I started climbing in the first place.

I don't romanticize the path I took. Dropping out twice wasn't some rebellious masterstroke; it was messy and confusing and often felt like failure. But it also gave me perspective. I learned to respect structure without blindly submitting to it, and I found a version of school that worked for me, eventually.

Now that I'm here, I still don't think the degree means that much. It opens doors, sure. But the things that have moved me forward—curiosity, persistence, building things that people actually use... those came long before the Ivy League. Credentials get you in the room, but they're not what make you valuable once you're there. And they're definitely not what make you whole.